Women (Not) in the Workforce During COVID-19

Due to the widespread closure of both schools and childcare providers in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, families with two working parents are now tasked with providing round-the-clock childcare and assisting in their childrens’ education, all while completing their jobs.

In many heterosexual households, either the man or woman has had to make the decision to leave their career or cut back on hours in order to take care of their children. While all parents have surely felt the effects of pandemic stress, one group has been disproportionately affected by the lack-of childcare crisis: Mothers.

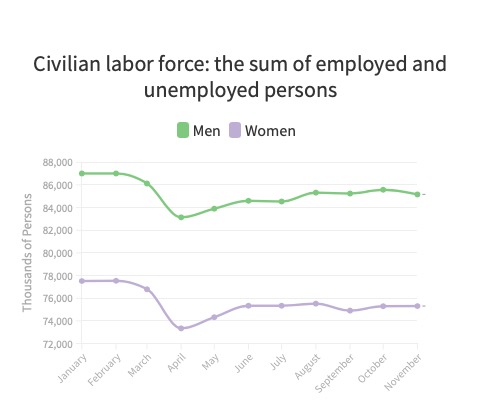

According to the U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics, women are exiting the workforce in staggering numbers. From August to September 2020, 617,000 women dropped out of the workforce while only 78,000 men dropped out during the same period. These statistics reflect the common pressure felt by mothers in heterosexual households to tend to their domestic duties in addition to their professional duties.

Meg Heckman, an assistant professor of journalism at Northeastern University who has completed research on women and their relationships with their employers, said that the wage gap is a huge factor in the likelihood that women leave the workforce over their male partners.

For every $1 made by a white man, a white woman will make $0.79, with Black and Hispanic women making even less, according to data from the Census Bureau. “If you look at what scenario is going to be the most likely to pay most of your bills and not have the kids fall too terribly behind on education, the person who is making less money quits her job or cuts back on her hours,” Heckman said.

Dalit Nobelman-Vaknin of Brookline, Mass. is a mother of two boys, ages four and six, and works from home alongside her husband, David Vaknin. Nobelman-Vaknin starts her work day around 5:30 a.m. so that she can catch up on work before she has to assist her children with their virtual school, making sure they stay on task, are completing their work, and are not wandering around the house.

When asked if she or her husband planned to alter their careers in order to accommodate the kids being at home, Nobelman said they were going to wait it out – but she knows she will be the one to make a career change if it comes down to it.

Aside from the pressure felt by women to either leave their jobs or to balance their careers in addition to their domestic responsibilities, there are several long and short term effects of this mass exodus of women from the workforce.

“We are at risk of losing tremendous amounts of talent, knowledge and diversity because of this,” Heckman said, referring specifically to the women leaving white-collar jobs. “We’re losing huge amounts of institutional memory and intellectual prowess because women are feeling forced to give up their jobs,” she said. In the short term, she added that these families are also at risk of falling behind on payments like student loans or mortgages.

On the other end of the spectrum, for mothers working in more socioeconomically challenged positions such as minimum wage jobs or gig work – the stakes may be much higher, Heckman said. These mothers may not be able to afford to quit their jobs or cut back on hours, meaning they must balance basically two full-time jobs. In the short term, this stress can be detrimental to the mental health of mothers.

Heckman blamed the “terrible social safety net” in the U.S. for the lack of support for families during times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. As the COVID-19 vaccine is slowly distributed around the world, there is hope that American mothers can soon return to their jobs as their children return to school – and that the progress made by women in the workforce over the last century will not regress.